Thyroid Hormone Basics: How It Works, How It’s Regulated, and Why Holistic Care Matters

The thyroid makes two key hormones — T3 and T4 — that steer metabolic rate, cellular energy use, and many organ systems through the hypothalamus‑pituitary‑thyroid (HPT) axis. This article walks through thyroid anatomy, how T4 is converted to active T3 at the tissue level, and why balanced thyroid function matters for energy, temperature, heart rhythm, mood, digestion, fertility, and bone health. Many people feel vague symptoms — persistent fatigue, unexplained weight change, or slowed thinking — that trace back to subtle thyroid dysfunction or interacting issues like nutrient shortfalls, environmental toxins, or hormonal imbalance. Understanding the mechanisms helps clinicians choose the right tests and pursue true root‑cause care. You’ll learn how the gland produces hormone, how T3 and T4 act in cells, how TRH and TSH feedback maintain balance, common hypo‑ and hyperthyroid patterns, and practical integrative strategies clinicians use to support thyroid health. We also clarify key lab distinctions — free versus total hormones, reverse T3, and central versus primary causes — so you can read a thyroid panel with more confidence and know when to seek a personalized clinical evaluation.

What is the Thyroid Gland and Its Role in Metabolism?

The thyroid is a small endocrine gland in the lower front of the neck that produces iodinated hormones with broad, systemic effects. Follicular cells synthesize thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) by iodinating and coupling tyrosine residues on thyroglobulin, while parafollicular C cells secrete calcitonin to help regulate calcium. T3 and T4 bind nuclear receptors in tissues to increase expression of metabolic enzymes and mitochondrial function. Because thyroid output directly changes ATP turnover and thermogenesis, even modest shifts in hormone levels can alter weight, energy, and functional capacity. Clinically, enlargement (goiter) or nodules may signal compensatory growth, autoimmune inflammation, or iodine imbalance; palpation and imaging help guide evaluation. Grasping this anatomy and physiology makes clear why targeted testing and interventions can restore metabolic balance and relieve symptoms.

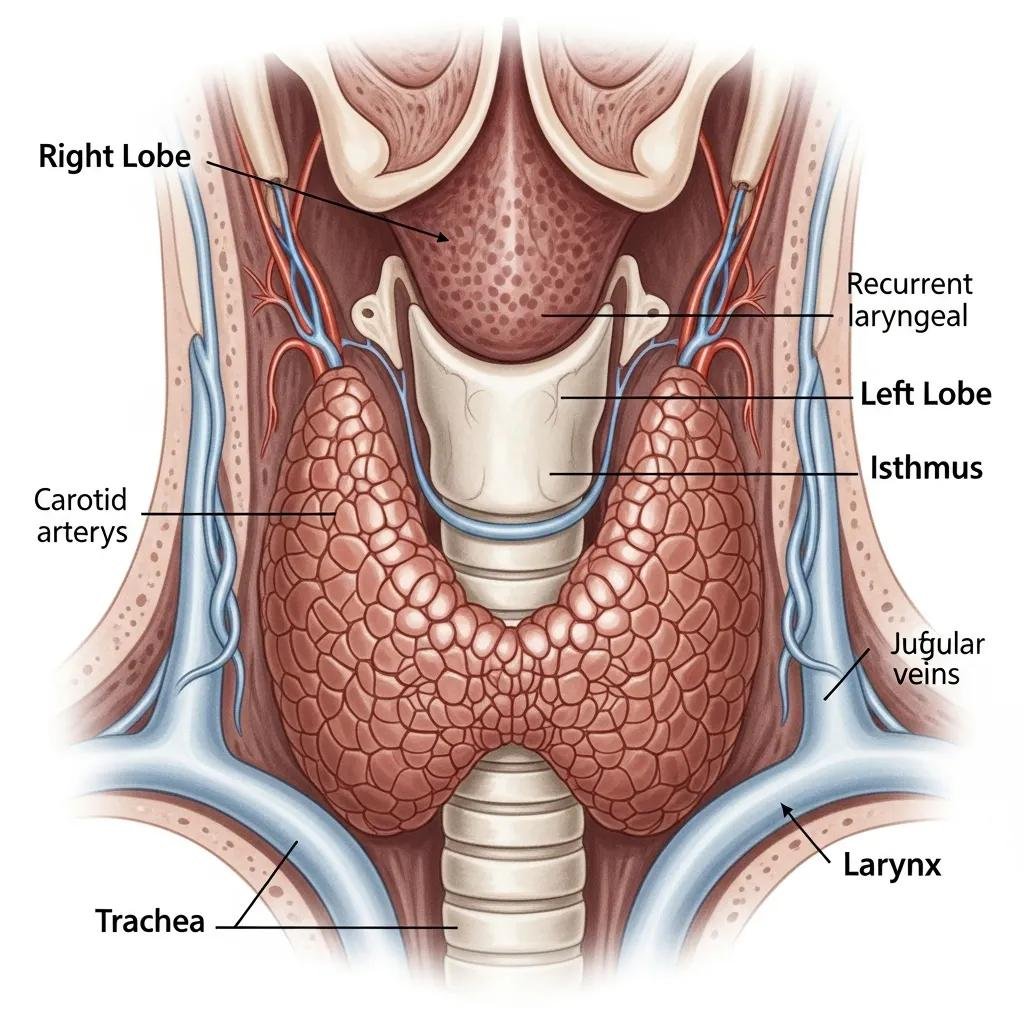

Where is the thyroid gland located and what is its anatomy?

The thyroid sits low in the front of the neck over the trachea (roughly C5–T1). It has two lobes joined by an isthmus and sometimes a pyramidal lobe. Microscopically, follicles lined with follicular cells produce thyroglobulin and concentrate iodine; the colloid inside follicles stores iodinated precursors used to make T4 and T3. Parafollicular (C) cells between follicles produce calcitonin, which modulates calcium but plays a smaller role than parathyroid hormone in human calcium balance. Clinically, asymmetry, nodules, or enlargement prompt imaging and labs because structural findings often accompany functional problems like autoimmune thyroiditis or nodular disease. This anatomical context helps explain how hormones made here change whole‑body metabolism.

How does the thyroid gland influence metabolic processes?

Thyroid hormones increase mitochondrial enzymes and uncoupling proteins, raise oxygen consumption, and speed carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. At the cellular level, T3 binds thyroid hormone receptors to change gene transcription, promoting mitochondrial biogenesis, higher ATP turnover, and heat production — all of which raise basal metabolic rate. Those cellular effects show up systemically as altered heart rate, gut motility, cholesterol handling, and core temperature. Low thyroid activity slows metabolism and can cause weight gain; excess hormone speeds metabolism and often causes weight loss and heat intolerance. That’s why tracking free T3 and free T4 along with TSH gives a fuller picture of tissue‑level hormone action. These metabolic roles set the stage for comparing the specific functions of T3 versus T4.

How Do T3 and T4 Hormones Function in the Body?

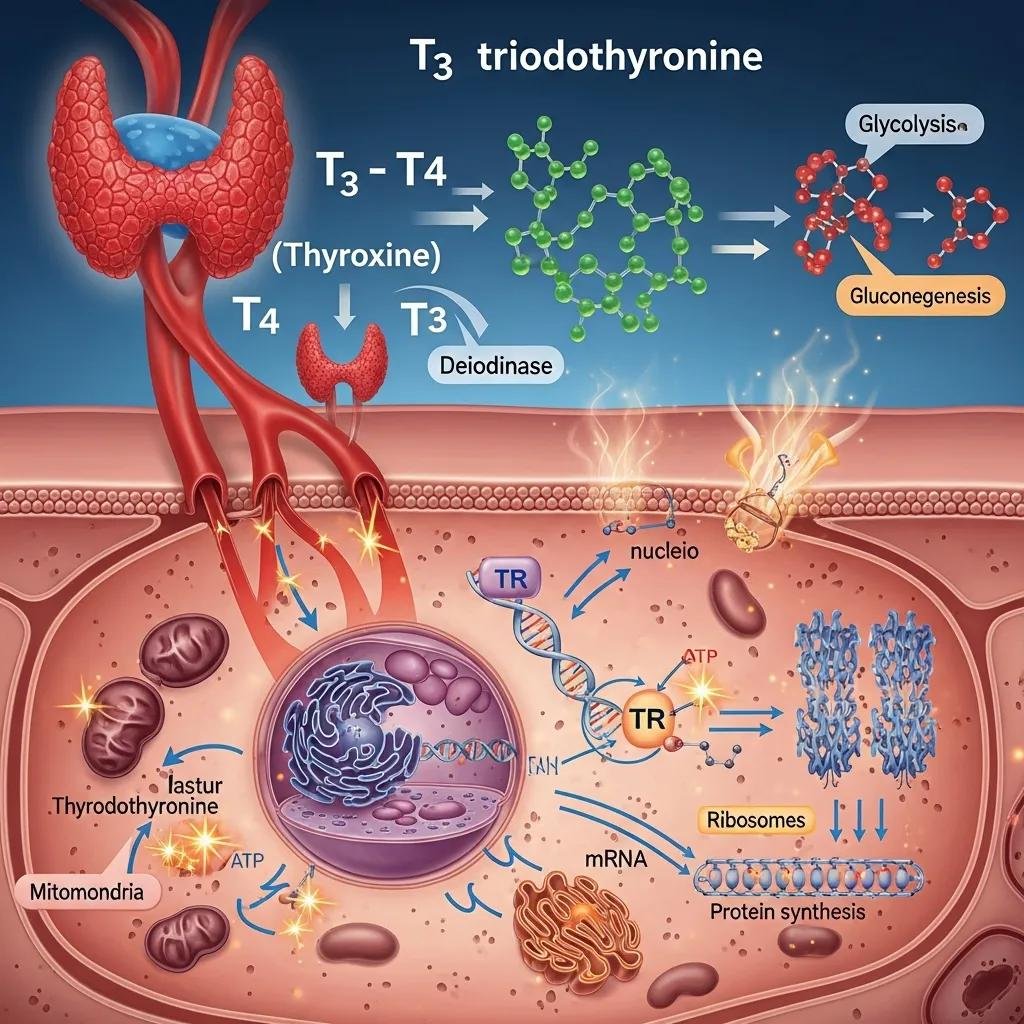

T4 and T3 differ by where they come from, how they circulate, and how potent they are. The thyroid secretes mostly T4, which serves as a circulating prohormone; most active T3 is produced in peripheral tissues by deiodinase enzymes that remove an iodine atom from T4. T3 binds receptors more tightly and acts faster but has a shorter half‑life; reverse T3 (rT3) is an inactive isomer formed in certain states (illness, stress) and can signal altered peripheral conversion. Clinically, measuring free T4 and free T3 — not just total levels — helps distinguish central versus peripheral problems and can explain persistent symptoms when TSH looks normal. These distinctions inform diagnostic choices and individualized treatment planning.

Below is a concise clinical comparison to clarify synthesis and activity.

| Hormone | Primary Source / Synthesis | Activity & Clinical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| T4 (thyroxine) | Principal secretion from follicular cells; made by iodination and coupling on thyroglobulin | Mostly protein‑bound in blood; longer half‑life (~7 days); serves as a prohormone converted to T3 peripherally |

| T3 (triiodothyronine) | Small direct thyroidal output plus major peripheral conversion from T4 | Active form with higher receptor affinity and greater potency; shorter half‑life (~1 day) |

| Reverse T3 (rT3) | Produced by alternate deiodination pathways during stress or illness | Inactive isomer; elevated rT3 suggests reduced peripheral activation of T4 → T3 |

This summary shows how synthesis and peripheral conversion shape hormone availability and why free hormone measurements better reflect tissue exposure. Those concepts lead into clinical relevance and how T3/T4 data inform personalized care.

For clinicians and patients, recognizing biochemical differences between T3 and T4 affects diagnosis and treatment. When free T3 is out of step with free T4 or TSH, it can indicate impaired conversion, illness‑related changes, or medication effects — patterns that may prompt reverse T3 testing or broader metabolic panels. At Internal Healing and Wellness MD, Dr. Fred Bloem applies a patient‑centered approach to interpret thyroid panels in the context of nutrition, toxin exposures, and broader endocrine balance, delivering tailored assessments and coordinated care from our Kensington practice. Detailed testing and a personalized plan clarify whether thyroid‑specific therapy, nutrient repletion, or broader hormonal optimization is most appropriate.

What are the differences between T3 and T4 hormones?

T3 is the biologically active hormone with higher receptor affinity and a shorter half‑life; T4 functions mainly as a circulating prohormone that tissues convert to T3. Because most circulating hormone is protein‑bound, free T3 and free T4 are better indicators of active hormone available to tissues. Tissue deiodinases control local activation or inactivation. Conditions such as nonthyroidal illness, chronic stress, or selenium deficiency can blunt conversion and raise reverse T3, producing hypothyroid‑like symptoms even when TSH is normal. Knowing these differences helps clinicians decide when to measure free fractions, check rT3, or consider combination approaches that address peripheral conversion as well as central regulation.

How do T3 and T4 regulate energy production and metabolism?

T3 regulates gene programs that drive mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and thermogenic proteins, increasing ATP turnover and heat production. This upregulation enhances enzymes that process carbohydrates and fats, raises beta‑oxidation, and increases resting energy expenditure — effects that influence weight, heart rate, and temperature regulation. Elevated thyroid hormone raises cardiac output and respiratory drive; low thyroid slows these systems. Clinically, this explains why correcting blood hormone levels alone may not fully restore metabolic function if peripheral conversion, nutrient status, or other hormonal imbalances are not addressed.

How is Thyroid Hormone Regulation Controlled by the HPT Axis?

Thyroid hormone levels are governed by a tightly regulated negative feedback loop: the hypothalamus releases TRH, TRH stimulates pituitary TSH release, and TSH drives thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion. Circulating T3 and T4 feed back on both the pituitary and hypothalamus to limit further TRH/TSH release. Clinically, TSH is a sensitive first‑line screen because small changes in free hormone prompt larger proportional shifts in TSH. However, central disorders of the pituitary or hypothalamus require direct measurement of free T4 and careful clinical correlation. Interpreting isolated lab values without feedback context can be misleading; the regulatory architecture underscores the value of integrating labs with symptoms and history.

What roles do the hypothalamus and pituitary gland play in thyroid regulation?

The hypothalamus integrates signals — temperature, stress, circadian rhythms — and releases TRH to regulate pituitary output. The anterior pituitary then secretes TSH, which stimulates follicular cells to increase iodine uptake and hormone production via cAMP‑mediated pathways. Circulating T3 and T4 inhibit TRH and TSH to maintain an individualized setpoint. Dysregulation at the hypothalamic or pituitary level (for example, pituitary adenomas or altered central signaling) causes secondary/tertiary hypothyroidism, where TSH is low or inappropriately normal despite low peripheral hormones. Identifying central causes prompts expanded endocrine testing and changes the therapeutic approach and expectations.

How does the feedback loop maintain thyroid hormone balance?

Negative feedback preserves hormone balance: rising T3/T4 suppress TRH and TSH to lower thyroid output, while falling hormones disinhibit TRH/TSH to raise production, creating a personalized setpoint. Individual variation in setpoint — due to genetics, receptor sensitivity, deiodinase activity, and transport proteins — explains why identical lab values can produce different symptoms in different people. Acute illness, certain medications, or stress can transiently change deiodinase activity, lowering peripheral T3 and raising rT3 while TSH remains normal; this pattern deserves cautious, longitudinal assessment rather than immediate hormone replacement. Understanding these dynamics supports repeat testing, broader panels, and attention to conversion pathways for more accurate diagnosis and tailored care.

What Are the Effects of Thyroid Hormones on Different Body Systems?

Thyroid hormones influence the cardiovascular, nervous, digestive, reproductive, skeletal, and integumentary systems by modulating metabolic rate, receptor expression, and tissue‑specific gene programs. They increase heart rate and contractility; they shape brain development, cognition, and mood; they regulate gut motility; they interact with sex hormones to affect fertility and menstrual function; and they accelerate bone turnover, with long‑term excess raising fracture risk. Clinically, these multisystem effects create recognizable symptom clusters that help direct testing and treatment priorities. A comprehensive approach to thyroid care considers cardiac safety, neurocognitive function, reproductive planning, and bone health alongside endocrine correction.

How do thyroid hormones impact metabolism, heart rate, and brain function?

Thyroid hormones raise basal metabolic rate by increasing mitochondrial enzymes and uncoupling proteins, which boosts resting energy expenditure and oxygen consumption. In the heart, T3 upregulates beta‑adrenergic receptors and improves contractility, explaining tachycardia and palpitations when hormones are high and bradycardia with low hormone states. In the brain, thyroid hormones are essential for development (neuronal migration and myelination) and in adults they affect neurotransmitters, processing speed, and mood — hypothyroidism commonly causes slowed thinking and depressive symptoms, while hyperthyroidism often leads to anxiety and agitation. These links explain why metabolic, cardiac, and cognitive complaints frequently appear together and why coordinated evaluation across systems is valuable.

What is the influence of thyroid hormones on digestion, fertility, and bone health?

Thyroid hormones modulate gut motility, reproductive hormone interactions, and bone remodeling. Hypothyroidism typically slows transit and can cause constipation; hyperthyroidism accelerates transit and may cause diarrhea. Thyroid dysfunction alters sex hormone binding and gonadotropin interactions, contributing to menstrual irregularities, infertility, and pregnancy risk — so optimizing thyroid status is part of preconception care. For bone, excess thyroid hormone speeds turnover and increases fracture risk over time, while hypothyroidism may lower remodeling; long‑term management should include bone density monitoring when indicated. These interconnections make it important to recognize common patterns of imbalance and their systemic effects.

- The following systems are commonly affected by thyroid hormone status:Cardiovascular: heart rate, contractility, blood pressure regulation.

Neurological: cognition, mood, development, and peripheral nerve function.

Metabolic & Digestive: basal metabolic rate, weight regulation, gut motility.

These system‑wide effects are one reason thyroid evaluation often benefits from a multidisciplinary lens that coordinates cardiac, reproductive, and bone health surveillance. Understanding these links helps clinicians prioritize tests and interventions based on the patient’s dominant concerns.

What Are Common Thyroid Imbalances and Their Symptoms?

Thyroid disorders generally present as hypothyroidism (too little hormone action) or hyperthyroidism (too much). Each has typical causes, characteristic lab patterns, and symptom clusters that inform diagnosis and treatment. Common causes include autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s) leading to gradual hypothyroidism, Graves’ disease causing antibody‑mediated stimulation and hyperthyroidism, iodine deficiency or excess, transient thyroiditis, surgical or radioiodine ablation, medications that alter synthesis or conversion, and central causes from pituitary or hypothalamic dysfunction. Hypothyroidism often causes fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, constipation, hair loss, and low mood; hyperthyroidism commonly causes weight loss, heat intolerance, tremor, palpitations, anxiety, and diarrhea. Both can include red flags that need urgent care. Focused symptom clusters plus targeted labs — TSH, free T4, free T3, and selective antibodies — help differentiate causes and guide next steps.

Use the quick reference below for common lab patterns and symptom clusters during initial triage.

| Diagnostic Category | Typical Labs | Common Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothyroidism (primary) | High TSH, low free T4 | Fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, constipation |

| Hyperthyroidism (primary) | Low TSH, high free T4/free T3 | Weight loss, palpitations, heat intolerance, anxiety |

| Central (secondary/tertiary) | Low or inappropriately normal TSH, low free T4 | Fatigue, low libido, possible other pituitary hormone deficiencies |

This snapshot helps clinicians and patients interpret initial panels; follow‑up testing (antibodies, imaging) clarifies cause and directs therapy. Identifying underlying etiology ties directly into treatment choices and functional strategies to address modifiable contributors.

What causes hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism?

Common causes of hypothyroidism include autoimmune destruction (Hashimoto’s), surgical or radioiodine ablation, medications that interfere with synthesis, and central pituitary or hypothalamic dysfunction; iodine deficiency remains a cause in parts of the world. Hyperthyroidism frequently results from autoimmune stimulation (Graves’ disease), toxic multinodular goiter, thyroiditis with transient hormone release, or excess exogenous thyroid hormone; medication effects and rare TSH‑secreting pituitary adenomas are less common. Functional and environmental contributors — nutrient shortfalls (iodine, selenium, iron), chronic infections, toxin exposures, and gut dysbiosis — can influence autoimmunity and peripheral conversion, and are considered in a root‑cause evaluation. Understanding causes enables clinicians to combine targeted medical therapy with strategies that address modifiable factors.

- Common causes include:Autoimmune disease: Hashimoto’s (hypothyroidism) and Graves’ (hyperthyroidism).

Iodine imbalance: deficiency or excess can impair synthesis.

Structural or iatrogenic: surgery, radioiodine, and medications affecting synthesis or conversion.

How do symptoms of thyroid imbalances manifest in the body?

Thyroid dysfunction produces clusters of symptoms across energy, weight, mood, cardiovascular, skin/hair, and digestive domains that help clinicians recognize the problem. Hypothyroid clusters often include persistent fatigue, unexplained weight gain, cold sensitivity, dry skin, hair thinning, constipation, and low mood. Hyperthyroid clusters often include unintentional weight loss, heat intolerance, palpitations, more frequent bowel movements, nervousness, and tremor. Both extremes can affect fertility and raise cardiovascular risk. Red‑flag presentations — severe tachycardia or arrhythmia, high fever with agitation (thyroid storm), or profound hypotension and hypothermia (myxedema coma) — require emergency care. Evaluating symptom clusters alongside labs and context (medications, recent illness, pregnancy) helps set urgency and appropriate interventions.

- Key symptom lists for quick reference:Hypothyroid: fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance.

Hyperthyroid: palpitations, weight loss, heat intolerance.

Red flags: high fever with agitation, severe bradycardia or hypotension, altered consciousness.

How Can Holistic and Functional Medicine Support Thyroid Health?

Functional and holistic care focuses on root causes — nutrition, environmental toxins, gut health, stress physiology, and endocrine interactions — while integrating evidence‑based therapies and individualized plans. Practitioners often broaden the diagnostic workup beyond standard panels to include nutrient testing (iodine, selenium, iron, vitamin D), assessment of peripheral conversion (free T3, rT3), thyroid antibodies, and screening for environmental or gut contributors that affect immune and endocrine function. Interventions prioritize nutrient repletion, anti‑inflammatory dietary strategies, targeted supplements, stress and sleep optimization, toxin reduction, and, where appropriate, adjunctive services such as IV nutrient therapy or supervised detox protocols to support cellular recovery. This integrative approach treats the person, not only numbers, and coordinates thyroid‑directed treatment with systemic care to improve outcomes.

The table below maps common root contributors to functional interventions used in integrative thyroid care.

| Root Contributor | Potential Impact on Thyroid | Functional Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental toxins | Can disrupt hormone synthesis and peripheral conversion | Detoxification strategies, exposure reduction, lifestyle changes |

| Nutrient deficiencies | Impair iodination and deiodinase activity | Targeted supplementation (iodine, selenium, iron, vitamin D) |

| Gut dysbiosis / inflammation | Influences autoimmunity and nutrient absorption | Gut‑healing protocols, probiotics, anti‑inflammatory diet |

What holistic approaches address root causes of thyroid imbalances?

Practical holistic steps include ensuring adequate iodine, selenium, iron, and vitamin D; adopting anti‑inflammatory dietary patterns that support gut integrity; evaluating and treating gut dysbiosis when present; and reducing environmental toxin exposures that can interfere with endocrine function. Stress reduction, sleep optimization, and autonomic regulation (for example, breathwork and paced activity) influence the HPT axis and peripheral conversion, so these lifestyle interventions often complement nutritional strategies. Case management typically pairs these lifestyle and environmental interventions with targeted labs and longitudinal monitoring to assess response before and during any medication adjustments. Addressing root causes can reduce symptom burden and improve outcomes with targeted thyroid therapies.

- Evidence‑based holistic tactics include:Nutrient repletion: correct deficiencies to support hormone synthesis and conversion.

Gut and immune support: reduce inflammation to limit autoimmune progression.

Toxin mitigation and lifestyle changes: lower exposures that interfere with endocrine function.

How does bioidentical hormone replacement therapy benefit thyroid function?

Bioidentical hormone replacement therapy (BHRT) typically targets sex‑hormone and age‑related endocrine changes rather than replacing thyroid hormone directly, but optimizing the broader hormonal environment can reduce overlapping symptoms and improve metabolic responsiveness. In practice, BHRT may help with fatigue, mood, and metabolic slowdown that sometimes coexist with thyroid issues, enhancing quality of life when used alongside thyroid‑specific assessment and treatment. BHRT should follow individualized evaluation — including thyroid panels, reproductive hormone assessment, and a discussion of risks and benefits — and when included, it becomes part of an integrated plan rather than a substitute for indicated thyroid replacement. At our practice, BHRT is offered as one component of a patient‑centered strategy to restore balanced endocrine function under close monitoring.

For patients seeking integrated endocrine care, Internal Healing and Wellness MD provides individualized evaluations that may include BHRT when appropriate, along with targeted testing and supportive therapies such as IV nutrient support and detoxification programs to address systemic contributors. Our providers collaborate with each patient to decide whether BHRT complements thyroid care and to design safe, monitored protocols tailored to clinical goals and risk profile.

If you’re ready to pursue a personalized evaluation, Dr. Fred Bloem at Internal Healing and Wellness MD offers comprehensive integrative assessments that combine thyroid testing, nutrient evaluation, and review of environmental and adrenal factors into a customized care plan from our Kensington practice. To request a personalized evaluation, contact the practice to schedule an appointment and discuss a coordinated approach that addresses root causes and supports endocrine balance.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the common tests used to evaluate thyroid function?

Standard tests include TSH, Free T4, and Free T3. TSH is the usual first‑line screen because it reflects pituitary response to circulating thyroid hormone. Free T4 and Free T3 show the unbound, active hormone available to tissues. Additional tests may include thyroid antibodies to identify autoimmune disease and Reverse T3 to assess peripheral conversion. Together, these tests help clinicians diagnose hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and conversion disorders and guide appropriate treatment.

How can diet influence thyroid health?

Diet matters for thyroid health because certain nutrients are essential for hormone synthesis and conversion. Iodine is required to make thyroid hormones; selenium supports deiodinase enzymes that convert T4 to T3; zinc and iron also play roles. Most people support thyroid health with a balanced, whole‑food diet that includes adequate protein and healthy fats. While cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, kale) contain compounds that can interfere with thyroid function if eaten in very large amounts during iodine deficiency, they’re generally safe in a varied diet. Individual needs vary, so targeted testing and guidance can help optimize nutrition for thyroid support.

What lifestyle changes can support thyroid function?

Key lifestyle supports include regular physical activity, stress management, and consistent, restorative sleep. Exercise helps regulate metabolism and improves energy; practices such as mindfulness, yoga, or breathwork lower chronic stress and can favorably influence the HPT axis; and good sleep hygiene supports overall hormonal balance. Combined with nutrient‑dense eating and toxin‑reduction strategies, these lifestyle changes can enhance thyroid health and reduce symptom burden.

What role does stress play in thyroid health?

Chronic stress raises cortisol and can disrupt the HPT axis by reducing TRH and TSH secretion or altering peripheral conversion of T4 to T3. This can produce symptoms similar to hypothyroidism even when routine thyroid labs are within range. Managing stress with exercise, meditation, adequate rest, and targeted behavioral strategies is an important part of restoring hormonal balance and improving thyroid‑related symptoms.

How do environmental toxins affect thyroid function?

Environmental toxins — including heavy metals, pesticides, and endocrine‑disrupting chemicals — can interfere with thyroid hormone synthesis, disrupt the HPT axis, and impair peripheral conversion of T4 to T3. Some exposures may increase the risk of autoimmune thyroid disease. Reducing exposures (choosing cleaner personal‑care and household products, eating lower‑pesticide foods, and improving indoor air) and targeted detoxification strategies when appropriate can help protect thyroid health as part of a comprehensive care plan.

What are the potential side effects of thyroid hormone replacement therapy?

Thyroid hormone replacement is effective for many patients but can cause symptoms of excess hormone if dosing is too high — for example, increased heart rate, anxiety, weight loss, insomnia, and heat intolerance. Menstrual changes can occur as well. Regular monitoring of TSH, free T4/free T3, and symptoms is essential to adjust dose and minimize side effects. Patients should discuss concerns with their clinician so therapy is tailored and safely monitored.

Conclusion

Thyroid hormones are central to metabolism, energy, and the function of many organ systems. Recognizing signs of thyroid imbalance and understanding underlying causes allows for targeted testing and individualized care. A holistic approach — combining nutrition, lifestyle change, and targeted interventions when needed — often improves symptoms and long‑term outcomes. If you suspect a thyroid issue or want a deeper, personalized evaluation, consider scheduling a comprehensive assessment with a qualified healthcare provider.